By coincidence, I recently fell on one of those signs which give information about the time it takes for various materials that we use everyday to degrade. Apple cores, paper tissues, cigarette butts, chewing gum, cans, or plastic bags may thus take up to 500 years to decompose. However, among the most resistant materials, glass comes out far ahead since it sometimes takes up to 5,000 years to degrade. 5000 years … a lifetime roughly equal to its current age!

Glass work in Mesopotamia and Egypt

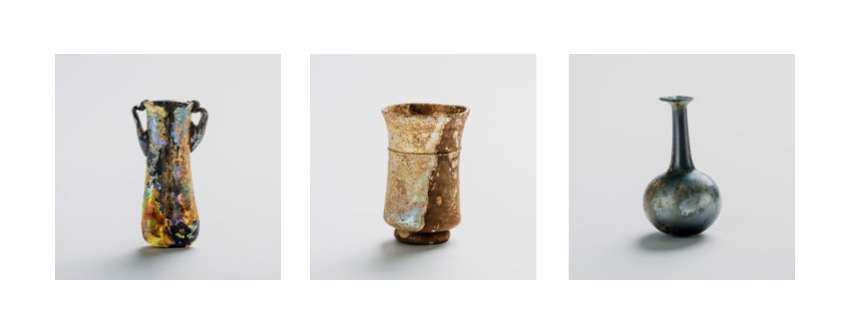

For although the exact date of its invention remains unknown – it is attested that during Stone Age already, men used obsidian, a natural glass of volcanic origin, for the manufacture of their tools – glass work is widely attested from ancient times in Mesopotamia and Egypt, before spreading to the entire Mediterranean basin. First considered a rare and expensive knowledge, glass making has now become an industry. Glass is so well integrated into our lives that we forget its presence; it is an essential element of our homes, of our vehicles, of our environment.

Did the craftsman who produced glass items in antiquity understand the importance of his gesture? Would he have imagined that this singular mixture – both so simple, because directly inspired by nature, and so complex, since glass work requires extraordinary precision – would open the door to thousands of glass objects of all kind through the ages? Did the Greek or Roman glass maker only suspect that the material he was holding in his hands would serve one day in the manufacture of view lenses, of watch glasses or even of aircraft windows?

Glass, a great invention

It is unlikely, although one would like to believe. For it is the same with glass as with all great inventions: they are born, often through some sort of miracle, then they escape their creator, they evolve, they grow up to become a marker in time, a way to measure history, a manner of looking at the world through a magnifying lens.

In our time of planned obsolescence, it is hard to imagine that the materials or objects we create, or the buildings we construct, can last at this point and survive us for so long. But again, maybe we are wrong … and future generations will have the chance to discover many vestiges of our civilization, with the same enthusiasm and passion that drives us in the study of objects of our past.

This question, however, no one can answer … unless having a glass crystal ball!

Martine Bouilloux